“What you encounter, recognize or discover depends to a large degree on the quality of your approach. Many of the ancient cultures practiced careful rituals of approach. An encounter of depth and spirit was preceded by careful preparation. When we approach with reverence, great things decide to approach us. Our real life comes to the surface and its light awakens the concealed beauty in things. When we walk on the earth with reverence, beauty will decide to trust us. The rushed heart and arrogant mind lack the gentleness and patience to enter that embrace.”

John O’Donohue

Let’s imagine you’ve found a story that you’re enraptured by and want to share. You know the story has something for you but you’re not sure how to approach it. I suppose there are two blunders we can make. The first is to want to run a workshop on it immediately - to teach. The other is to never share it at all.

It is my hope that the following, practical ideas can help you weave your way between those two dead-ends.

In the former approach, it’s easy, and understandable to hear a story a few times and think we’ve ‘got it’. But, if a story really grabs you and asks you to tell it and you want to honour it as deeply as you can, you could also consider the possibility of an extended courtship of the story. Not all of these are needed for every story. There are many on this list I’ve never done myself. But, for every one of these ways you explore, you will likely find that, rather than becoming more and more clear to you, the story becomes more and more mysterious.

Often we need to give up trying to find ‘the true meaning of the story’ and settle for the more useful reward of seeing ‘more’.

The simple, hardened moral you had imagined for it crumbles under your admiration and becomes something more useful–fertile soil for wondering into which the seeds of deeper inquiry can be planted and out of which can grow the very ‘mystery feast’ that Ben Okri writes of. Do not consider these approaches an attempt to banish mystery but a way of throwing elbows to give it some room to appear more fully.

Stories, like people, have layers upon layers. Like diamonds they are covered in different facets. The layers and facets we see depend on what the story wants to show us, based on the diligence and courtesy of our approach.

Consider your manner of approach to the story deeply. Stories are not resources to be plundered for insight and wisdom. As Martin Shaw put it, “A story wants to say to you, ‘You can’t stretch me on the rack of instant exegesis. I’m more mysterious than that!’” Stories are an entrustment. They’re something pointing us back to the world from whence they, and we, come.

And so, here are many ways of courting a story. May your growing capacity in this become the mystery feast for our great-great-grandchildren in the years to come.

But, the most important thought is one my friend James Nowak reminded me of, “Love is the most important thing.” Approach the story with love, high regard and admiration and the rest will help. Approach it without love and none of what follows will help.

Level One: Beginning To Learn The Story

Way #0 - Get A Mentor. More important than all of the others put together is to find someone deeply schooled in the old stories whose worldview you align with who can hold your hand and guide you into these old stories. I know of no one more capable than Stephanie Mackay.

I also recommend delving into the world of Comparative Mythology. The authors of many of these books are well dead now but there’s immense wisdom in them. There are many scholars who spent their lives comparing stories from one tradition to another and delving into the deeper meanings of these stories based on linguistics, etymology, philology, archaeology and cultural studies.

Myths and Mythmakers: Old Tales and Superstitions Interpreted by Comparative Mythology - John Fiske

Comparative Mythology - An Essay Max Muller, A. Smythe Palmer

Comparative Mythology - George Cox

Comparative Mythology - Jaan Puhvel

The Cave of the Sun - Adrian Bailey

Way #1 - Asking permission of the person from whom you heard it to tell it if you can. Ask them properly with the giving of gifts.

Way #2 - Find other versions of the same story. If it’s a Scottish story, find other versions from within Scotland. Find versions from other cultures. One of my favourite Scottish stories had an almost identical story in a book of Ukrainian stories. Many of these stories travel. Read those too and seek out what’s common in them all. Those are likely the most important bits. From Martin Shaw in WolfMilk, “Look at as many versions of the story through culture as you can find. If it talked about a whale road or a sword fight then go to the ocean or take up fencing– follow its lead. This pursuit is a sign of respect, that you take the story seriously. Just don't mistake that research or lines on paper as where the story really lives. It's more a gesture of decency and readiness.”

Way #3 - Read or listen to it multiple times. The first time is just for enjoyment. Many things won’t land for you until you’ve heard or read it many times. Some things not for years.

Way #4 - Look up terms you don’t understand. These old stories are describing a world that doesn’t exist anymore. They are full of terms that you may not understand and things you can’t picture. It’s important that, as a storyteller, you can clearly picture and describe the elements of the story and things we might find in it. Look them up. Do a brief study so, if someone asks you, “What’s that?” you can tell them.

Way #5 - Research core motifs, symbols and metaphors. Consider what different people feel they may mean. Read a dream analysis book’s description of it. Google it. Go to the library. Talk to that Jungian friend of yours. Track the symbolism of all the elements of the story. Get yourself some books of Symbolism. Here are some of my favourite:

A Dictionary of Symbols Juan Eduardo Cirlot

An Illustrated Encyclopaedia of Traditional Symbols J.C. Cooper

A Dictionary of Symbols J. E. Cirlot

The Herder Dictionary of Symbols

The Penguin Dictionary of Symbols Jean Chevalier

Dictionary of Symbols: Cultural Icons & The Meanings Behind Them Hans Biederman

The Women’s Encyclopedia of Myths and Secrets by Barbara G. Walker

The Woman's Dictionary of Symbols and Sacred Objects by Barbara G. Walker

Way #6 - Take your story for a walk. Once you’ve read the story enough times to have a grasp of it, take it for a walk. Move your body. Ruminate on the story. Get out into nature and let the story cook inside of you and work you.

Way #7 - Ask why they kept this story alive. In an oral culture, you can only remember and pass on so many things. This story survived, maybe for millenia, and this means it contained vital teachings for a traditional, land-based peoples. These stories are older than our modern political and psychological axes we’d grind on it.

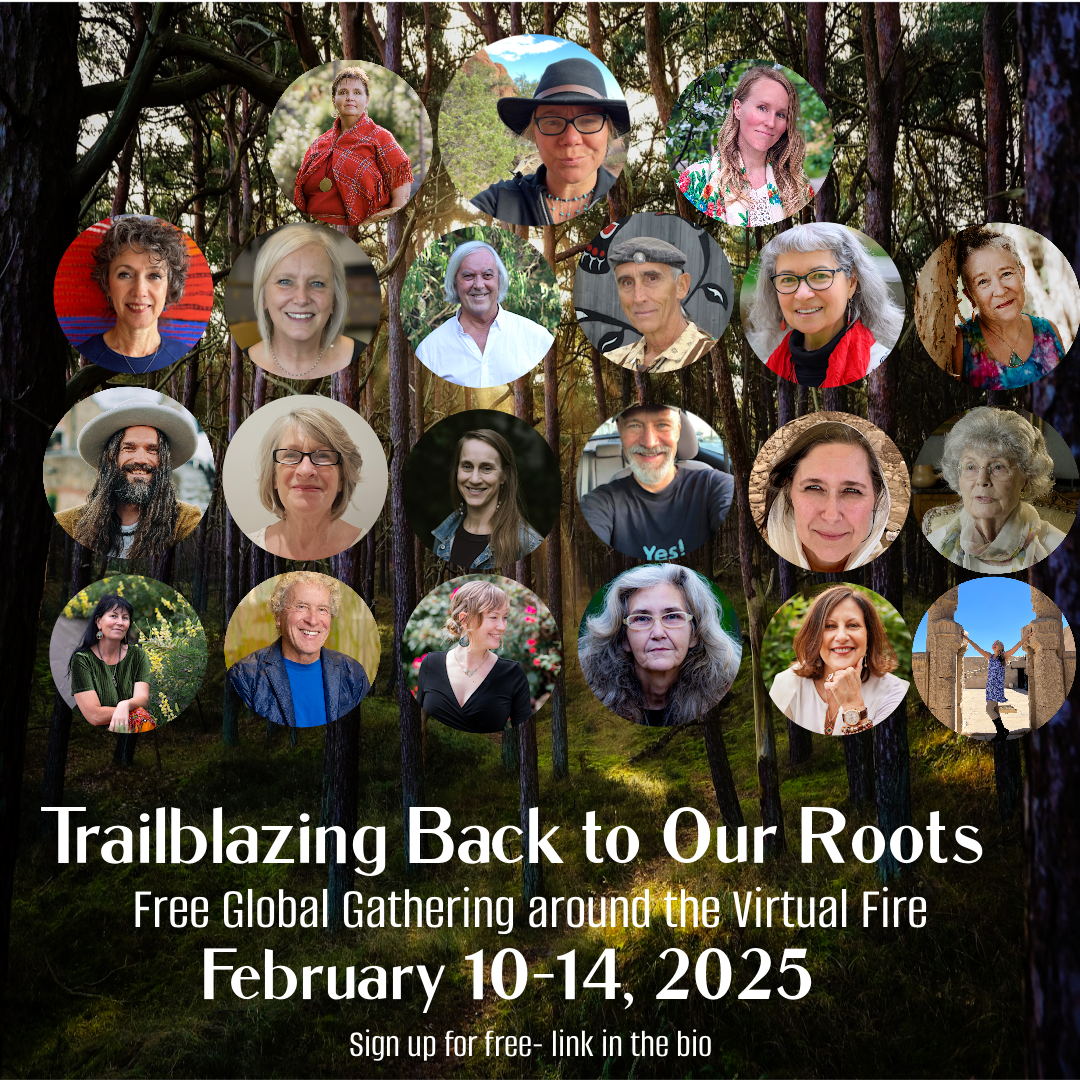

I’ll be presenting in this but the whole thing is worth it just for the appearance of Stephanie Mackay.

All the money raised from your pledges to this Substack go to support the work of indigenous, cultural activist Kakisimow Iskwew.

We are offering our Briar Rose & The Indigenous Memory of Mother Europe in a variety of formats including live, four-hour sessions in BC and Alberta.

She’s also offering her own Digging Roots cross cultural programs.

Learn more, get tickets or join the email list at the link below.

Thank you for this and for your work in this world.

Beautiful. Thank you, hermano, for this wee offering and the grand commitments that lay beneath them. Peace! Bless!